ALERT

ALERT

![]()

VOICE FROM THE

FIELD

VOICE FROM THE

FIELD

“We could see villages

burning all along the road”

“We could see villages

burning all along the road”

An

ongoing conflict in the

This is Matte’s account of his mission in

It was around

It was around

I

touched down in Khartounm on December 28 and spent seven days there waiting for

travel permit so I could join the Doctors Without

Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières

(MSF) team of four international staff in Nyala. I met up with the team just as the Sudanese

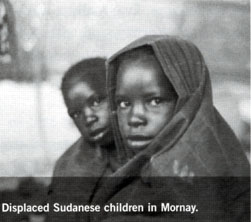

authorities were pressing for the relocation of a group of 10,000 internally

displaced persons (IDP’s), who had gathered thee and

in nearby Intifacah camp to a new location about 10

miles away in Belel.

Children under five were estimated to be dying at a rate of 6 per 10,000

per day – six times the death rate used to designate an emergency. The team was providing basic food assistance

and health care services to the population.

Most of the IDP’s had nothing more than sticksto create shelter for themselves. The temperatures could reach 90 degrees

during the day , then fall to 40 degrees at night.

The

IDP’s in Nyala and nearby Intifadah

camp represented just a fraction of the people forced from their homes since

fighting broke out between rebel and government forces in the greater

The

conditions in the new location, Belel, were abysmal -

three latrines and one manual water pump for

thousands. The area was completely

exposed to attacks from the Janjaweed, the horseack-riding militias that have unleased

a scorched-earth campaign against the civilian population throughout

I

cold only imagine the fear they felt

Most,

if not all of them had fled to Nyala and Intifadah after seeing their villages burned. Over the next 24 hours, all but about 500 of

the 10,000-plus people vanished into the bush.

Some were trucked to Belel while others fled

on foot.

With

no one left to help, all we could do was pack up and prepare to reach other

towns in desperate need of assistance.

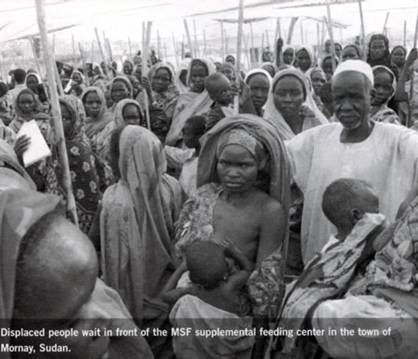

An MSF team went to evaluate the towns of Mornay, Zalinge,

and Garsilla – all swollen with an influx of people

driven from their villages. It was

decided that Coralie Lechelle,

a French nurse, and I would make our way to Mornay to provide assistance.

We

pulled ogether a team of 10 national staff (5

drivers, 2 nurses, a medical assistant, and 2 translators), and set off for

Mornay in a convoy of two MSF cars and five trucks loaded with drugs,

logistical supplies, and food. We

dropped our materials in Zalinge, northwest of Nyala,

and headed to El Genina, the regional capital of

I will never forget what I saw next

I will never forget what I saw next

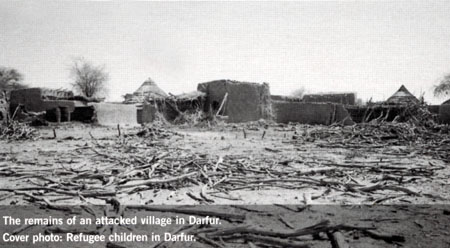

Village

after village along the road to El Genina had been

burned to the ground and abandoned.

Fleeing civilians lined the road.

Only three villages remained standing and their inhabitants appeared to

be waiting out the situation.

Once

we reached El Genina, the authorities gave quick

approval for us to work in Mornay. We

rushed back through Mornay to tell civilians that we would return to provide

assistance. They begged us to return quickly. On the road back to Zalinge

we saw the the villagers from Tulu,

Salulu, and Mara were fleeing with all the

possessions they could carry to Mornay or Zalinge. The Janjaweed had

told them that they would return to destroy their villages.

We

got back to Zalinge, where we spent the night. The next morning, we set up a pharmacy. Then we screened 5,00

children for malnutrition – one in ten was malnourished. When we arrived, about one-third of the

families had stocks of sourghum (a cultivated

grain). We started to treat the most

severe cases of malnutrition. Then over

the next thee days we vaccinated 5,000 children against measles – a disease the thrives on malnourished children liveng

in close quarters. We established a

clinic.

Then

the bombs started falling around Mornay

The

town of

When I wasn’t helping in the clinic, or trying to obtain

information on the security situation, I walked through the town asking new

arrivals about their villages and what had happened to them. They said that hundreds from each village had

been killed. They told stories of

children strangled, women burned alive, and men shot to death. Out of any group of 20 people, maybe one was

an adult male. Most of the men had been

killed or had stayed back to watch over food supplies. But the majority of the people had no idea

what had happened to their sons, husbands, and fathers.

When I wasn’t helping in the clinic, or trying to obtain

information on the security situation, I walked through the town asking new

arrivals about their villages and what had happened to them. They said that hundreds from each village had

been killed. They told stories of

children strangled, women burned alive, and men shot to death. Out of any group of 20 people, maybe one was

an adult male. Most of the men had been

killed or had stayed back to watch over food supplies. But the majority of the people had no idea

what had happened to their sons, husbands, and fathers.

There

was the constant fear that Mornay would be next; that they would “clean” the

town of all its inhabitants as had happened in countless other villages. Coralie and I spoke

every hour. We were constantly assessing

the danger and in contact with the MSF headquarters in

Finally,

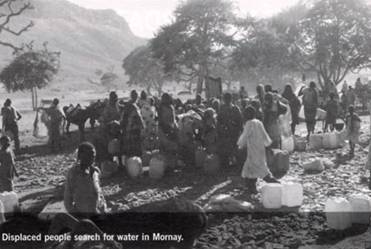

on February 16 the bombing stopped. By

then, there were close to 60, 000 people in Mornay. We were working against impossible odds. The streets were littered with dead donkeys,

sheep, and cattle. None of the people

had food for their animals, and it was still to dangerous for them to venture

outside of the town. I spent a good part

of my days leading efforts to bury dead animals to preven

outbreaks of disease.

We

were treating 300 severely malnourished children and prviding

supplementary food to 1,200 more. Eventuall a water and sanitation team was able to reach

Mornay, and with their help we were able to provide 500,00

liter of water per day to the population, or 10 liters per person.

When

Coralie and I left

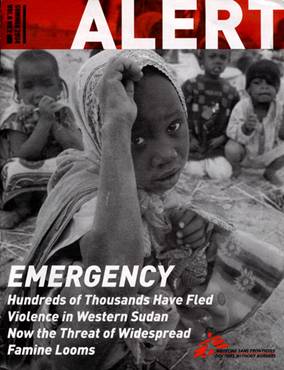

Emergency Update:

Famine

Looms in

A

recent NFS nutritional survey of children and their caregivers in five

locations in Drfu, where nearly 150,000 displaced

people have sought refuge from extreme violence, shows thet

the whole population is on the brink of mass starvation.

The

survey revealed a gloval acute malnutrition rate of

21.5 percent among the population (20 percent is an indicator of an

emergency). The study found the

mortality rate for children under five years of age to

be 5.2 dearths per 10,000 people per day, while the

rate for those over five year of age was 3.6 deaths per 10,000 people per day.

Both rates ar more thean double the emergency

thresholds, and although most of the children died from hunger, diarrhea, or

malaria, 60 percent of all deaths for those over five years of age were caused

by violence.

As of

June 1, there were nearly 50 MFS interational

volunteers in Darfjur working alongside hundreds of

Sudanese staff. MSF is providing medical

and nutritional assistance to people in Mornay and 10 other locations

throughout

Note: last month five of these noble champions were

killed in

Thank

you Jean Sébastièn Matte, …Ms Coralie Lechelle you are a lucky man, …and you are a lucky woman to

have these things you hold so dear in your heart. You have made a real difference in your world, …and your world is very proud of you.